09 Feb Medellin Colombia, from the world’s most dangerous to most innovative city

There are two bird statues in San Antonio Square in Medellin Colombia. One is discoloured and gnarled, destroyed by a bomb in 1995 that killed 22 people who were enjoying a music concert. The second bird is identical save for the fact that it’s shiny and whole. These Pajaros de Paz, Birds of Peace, are a stark reminder of Medellin’s troubled past, but also of its transformation from the most dangerous to the most innovative city in the world.

As our Colombian tour guide Pablo, who shares a name with Colombia’s infamous drug baron, told us the story of Fernando Botero’s birds, a swarm of police on motorbikes converged on the square. They stopped to search a group of men just a few feet from the statues and Pablo joked: “See how safe Medellin is these days?” But that’s the thing, Medellin is so much safer than it used to be.

The murder capital of the world

Twenty years ago, this free walking tour wouldn’t have existed, this group of European, American and Argentinian tourists wouldn’t even have been in Colombia. In 1988, Time Magazine dubbed Medellin the most dangerous city in the world, home to Pablo Escobar’s notorious drug cartel and in the early 90s, its murder rates were staggeringly high. Our guide Pablo, who is just a few years younger than us, remembers walking to school in those days and seeing dead bodies on the street.

Now, as Pablo leads us through the squares and streets of the central district, local people call out: “Hello Gringos!” as we pass. The city is a hive of commerce, busy with shops and street stalls selling everything from electronics to clothes and watches. There are empanada and arepa stalls and vendors selling cups of cold sugarcane and lime juice. In Parque Berrio, musicians gather for evening jamming sessions and people of all ages rock up to dance.

Medellin Colombia transformed

After decades of messy war and politics, which Pablo briefly explained to us but I have barely the slightest grasp of, the government has done an amazing job of transforming Medellin. Take Plaza las Luces, which once held the burnt shell of a market where homeless people lived. City planners tore it down and planted bamboo, they opened shelters and rehab centres and installed a forest of spiked poles that light up at night. Just off the square, Pablo showed us the secretary of education building that was once full of makeshift shacks where people with drug addictions lived.

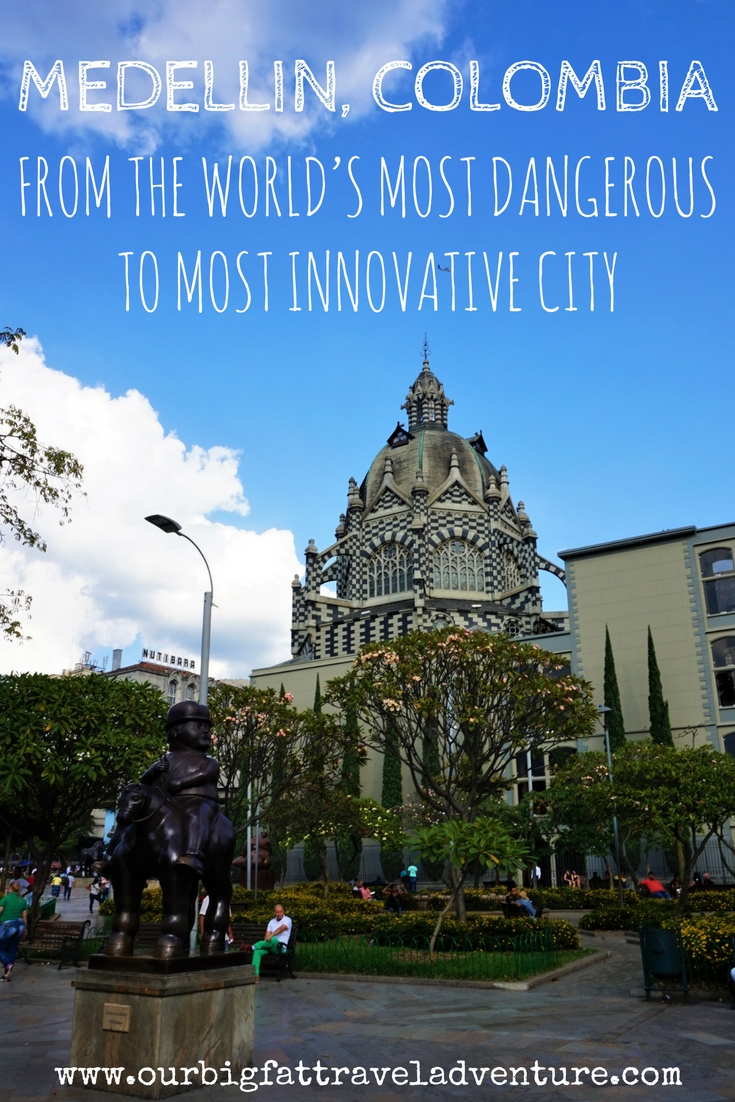

Medellin now boasts modern libraries, a cable car and a metro system that links all the once-isolated hillside communities to the city centre. These places used to be drug cartel strongholds and areas the police reportedly refused to go. The famous Colombian artist Botero donated 23 of his statues, worth millions of dollars, to the city and they sit proudly in a square named after him, alongside the checkerboard church-like Palace of Culture.

In 2013, the Urban Land Institute named Medellin the world’s most innovative city for its incredible turnaround. Yet, as Pablo explained to us, this transformation is fragile. While there’s less violence now, there are still gangs and street crime has risen. We saw people collecting signatures for a petition against the government’s peace agreement with FARC. According to Pablo, people take crack in Bolivar Square right next to the police station. Outside Veracruz Church, sex workers wait for customers in broad daylight. There are soldiers with guns and police men in florescent vests everywhere.

It’s confusing, Medellin.

Our month in Medellin Colombia

When we first arrived here last weekend and took a trip into the city centre, I admit that we didn’t feel comfortable. I certainly wouldn’t walk around at night on my own, the same way I would in cities like London, Hanoi or Chiang Mai. However, hearing Pablo talk so vividly about what life used to be like in Medellin, I was awed by how the city had managed to reinvent itself. I was humbled by how happy and welcoming the people are and I was moved by the way Pablo spoke about his country, its struggles and hopes for the future.

“People are happy to see you here,” Pablo told us, “because you’re a sign that Colombia is changing.”

Pin Me For Later!

Although I still feel terribly ignorant about Colombia’s culture and past, this incredible free walking tour (not sponsored by the way), really helped me start to make sense of Medellin Colombia. As we stay here for the next month, we’re hoping to learn even more about this bewildering, yet fascinating city.

Alyson Long

Posted at 06:30h, 10 FebruaryInteresting! Thanks 🙂 Enjoy Columbia, it’s something completely different for sure. How’s the food?

Amy

Posted at 16:42h, 10 FebruaryThanks for reading Alyson, yes Colombia definitely is different from anywhere else we’ve been. The food is very deep-fried and meaty! The local fruit and veg is amazing though and there are loads of beans, lentils, etc so we’re enjoying eating in a lot. We’ve also found a few vegan restaurants serving versions of Colombian dishes, which is nice. It’s definitely not as easy as Thailand though to be veggie or vegan!

Rhonda

Posted at 21:30h, 10 FebruaryI’m glad you’re enjoying the city. We have not yet been but know it’s now a favorite of many travelers as they continue to reinvent its image.

Amy

Posted at 21:50h, 10 FebruaryHi Rhonda, it’s definitely a city that’s changing fast and is unlike anywhere we’re ever been before. We’re still trying to get to grips with the place, but the expat area in El Poblado is a bit more relaxed.

Gilda Baxter

Posted at 15:14h, 12 FebruaryA walking tour is a great idea to get your bearings and learn from a local like Pablo…fascinating history. I have always heard that Medellin was a violent, dangerous city. But It is encouraging to hear that things are changing and the city is shedding its shady past. It will no doubt be a slow and long process. Brian and I will be in South America in June/July exploring Peru and Ecuador…we might bump into you?

Andrew Wyatt

Posted at 15:28h, 14 FebruaryIt is great to see the changes and even better to hear about them from a local’s perspective – it’s also nice to be a part of that change in some way. I doubt we’ll still be here in June, we’re thinking of heading to North America around that time, but of course, nothing’s decided yet! 🙂

Patti

Posted at 16:43h, 17 FebruaryVery interesting, Amy. I only know Columbia by its reputation – and not a good reputation – so I’m enjoying learning vicariously through you.

How was the government able to make this dramatic turn around? Did they take down the drug lord, was there some sort of revolution in that the people stood up to confront them problem, or was new leadership placed in office? I’m just curious. 😉

Amy

Posted at 16:52h, 17 FebruaryHi Patti, I’m glad you found the post interesting. It’s a really complicated issue and one I don’t know enough about. Briefly speaking though, from what I’ve learned, the government has really worked on making deals with the far right and extreme left factions. I believe that Juan Manuel Santos even got the Nobel Peace Prize for his deal with FARC (but it was rejected in a referendum and then amended and passed without a new referendum, so some Colombians are annoyed about that, from what I can gather). I previously thought that killing Escobar in the 90s radically improved things, but I’m not so sure now because when we visited district 13 this week the guide told us that the most violent years were those after he was killed, when factions were fighting for territory and power. It’s really complicated, there’s been lots of military action too. I think it’s still an on-going process and when it comes to the drugs, the demand from abroad is really a huge factor and one Colombia can’t control. It’s definitely been eye-opening staying here in Medellin.