Good Cause Dining in Cambodia

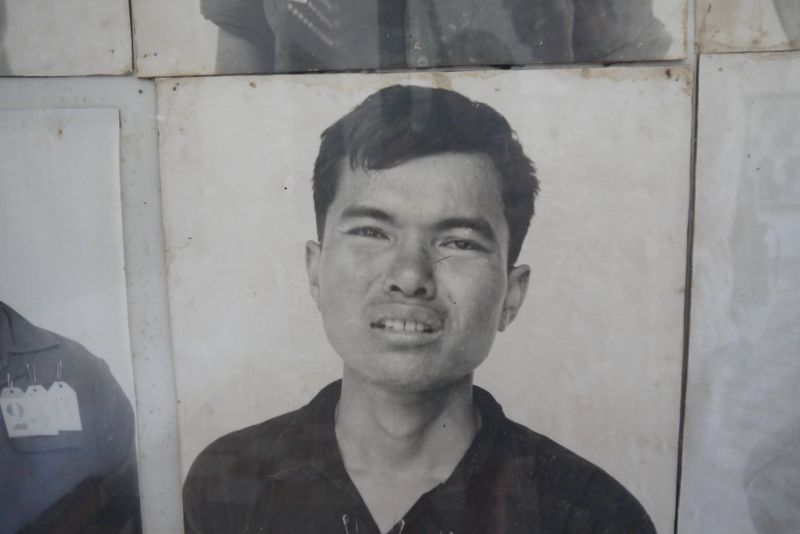

One of the hardest things about visiting Cambodia is witnessing the extreme levels of poverty that abound; from kids selling postcards at Angkor Wat to land-mine victims begging on the city streets. One of the best ways to help people in Cambodia is by eating in Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) restaurants which support and employ vulnerable groups of people throughout the country. Good Cause Dining is an all round win-win, your money and custom go to those who need it and you get a tasty meal in the process. 20 May, 2014 / 15 Comments